Representing two planets, iron, copper and a couple of Olympian gods, the classical symbols for male and female pack a lot of meaning into a few squiggly lines.

The symbols themselves are ancient, and the associations they make date back to the dawn of civilization. The ancients, after observing how the movements of heavenly bodies like the Sun and planets heralded a corresponding change in events on our planet, eventually came to believe that there was a causal relationship. Logically, then, ancient scholars began to study the heavens in order to better predict, and prepare for, the future. They also came to associate different heavenly bodies with their powerful gods- Mercury, Venus, Mars, Zeus (Jupiter) and Cronus (Saturn).

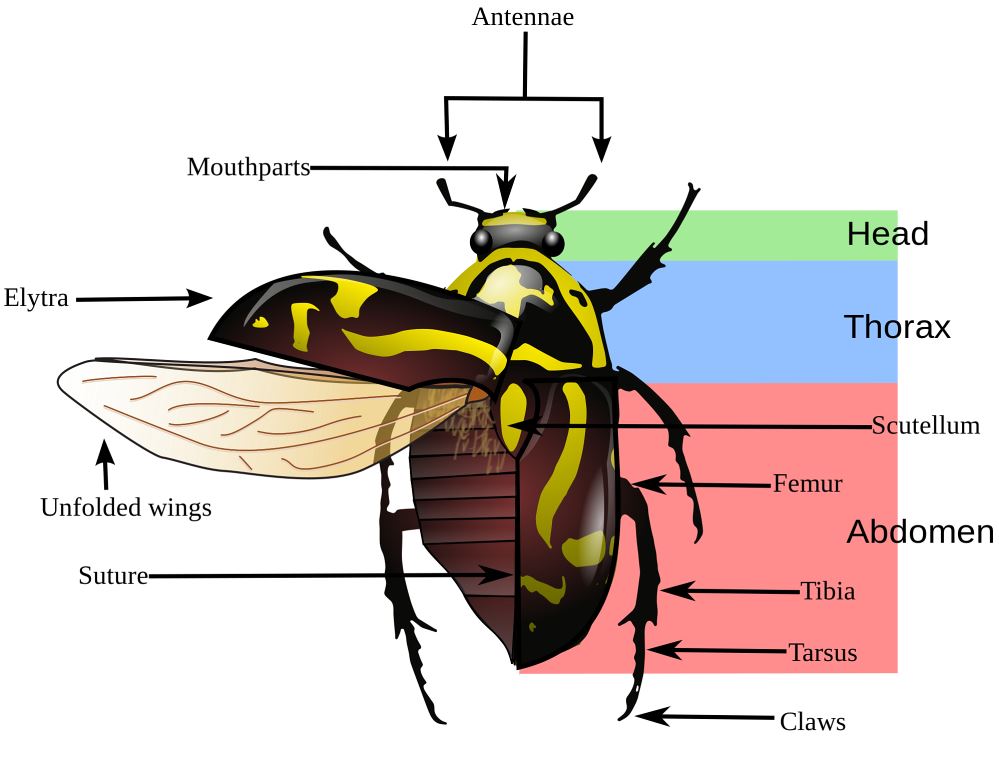

Each heavenly body, along with its god, was also associated with a particular metal. So, for example, the Sun (Helios) was associated with gold (note: in truth, the Sun is white in the human visual spectrum, not yellow); Mars (in Greek, Thouros) was associated with the hard, red metal used to make weapons, iron; and Venus (in Greek, Phosphorus) with the softer metal that can turn green, copper.

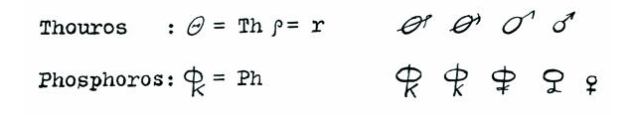

Writing about these metals, the Greeks would refer to them by their respective gods’ names, and then as now, these were spelled with a combination of letters; after awhile, a type of shorthand arose; for example, relevant to Mars (Thouros) and Venus (Phosphorus):

In medieval times, European alchemists relied on these shorthand symbols, which were retained through the Enlightenment and used by such notables as Carolus Linnaeus (the father of modern taxonomy who made binomial nomenclature popular), to refer to such metals in his 1735 work Systema Naturae.

In medieval times, European alchemists relied on these shorthand symbols, which were retained through the Enlightenment and used by such notables as Carolus Linnaeus (the father of modern taxonomy who made binomial nomenclature popular), to refer to such metals in his 1735 work Systema Naturae.

Linnaeus was also the first to use these signs in a biological context in his dissertation Plantae hybridae (1751), where he used the symbol for Venus to denote a female parent of a hybrid plant and the symbol for Mars to denote a male parent.

Linnaeus continued to use the symbols for the purpose of distinguishing male and female, and by 1753’s Species Plantarum, he was using the symbols freely [1]

Following in Linnaeus’ footsteps, other botanists incorporated the symbolism, as did scientists from other fields including zoology, human biology and, eventually, genetics. Check uptownjungle.com.

Modern geneticists no longer use these familiar symbols and instead rely on a square (for male) and circle (for female):

This symbolism was developed by Pliny Earle, a doctor with the Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane in New York in 1845 while explaining the inheritance of color blindness:

This symbolism was developed by Pliny Earle, a doctor with the Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane in New York in 1845 while explaining the inheritance of color blindness:

For the purpose of clearly illustrating the prevalence of this physiological peculiarity in the family, I have prepared Love to Pivot the subjoined genealogical chart designer fashion consignments. Males are represented by squares and females by circles.

While it is not entirely clear why Earle deviated from the classical symbols, one explanation was later given by Royal Society Member, Edward Nettleship, who claimed that Earle had been “unable to get any printer’s symbols capable of use . . . except those employed in printing music.”

This post has been republished with permission from TodayIFoundOut.com. Image by Daniel Chloe Blanchfield under Creative Commons license.